Historic Preservation

Preserving City Landmarks

1950-1965

Back to Exhibitions

On August 2, 1962, architect Philip Johnson, urban activist Jane Jacobs, and dozens of others picketed outside Pennsylvania Station to protest plans to tear down the 1910 Beaux-Arts masterpiece. Their campaign was the culmination of over a decade of struggle to protect city landmarks. Although they lost the battle over Penn Station, the building’s demolition helped lead to the passage of New York’s 1965 landmarks preservation law.

Following World War II, large swaths of the city were cleared to make way for office buildings, housing complexes, and roads. While some considered this progress, a small but influential group of activists warned of the loss of New York’s cultural and historic heritage. The Municipal Art Society and other groups fought the efforts of developers, including City Construction Coordinator Robert Moses, to tear down “landmark” structures.

But it wasn’t until the Landmarks Preservation Law of 1965 that buildings could be legally protected. Not only did the law allow for the preservation of individual structures, it also became a tool for activists fighting to preserve the character of entire neighborhoods.

The law and its application remain contested topics. Affected property owners often point to the financial difficulties of adhering to the preservation law, and some preservation advocates have complained about insufficient landmark protection. But indisputably, New York activists helped make New York City, in the words of historian Anthony C. Wood, “the intellectual capital of the preservation movement.”

Meet the Activists

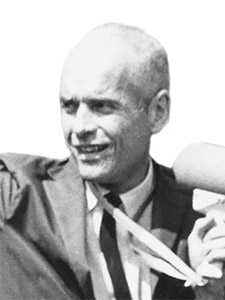

Clay Lancaster

Clay Lancaster

To arouse public interest and indignation at the threatened loss of Brooklyn Heights landmarks, historian Clay Lancaster presented slideshows and walking tours of historic buildings in Brooklyn Heights in the 1950s and 1960s. These endeavors helped open New Yorkers’ eyes to the neighborhood’s endangered architectural heritage.

Image Info: C. Binkins, 1966, Courtesy the Warwick Foundation.

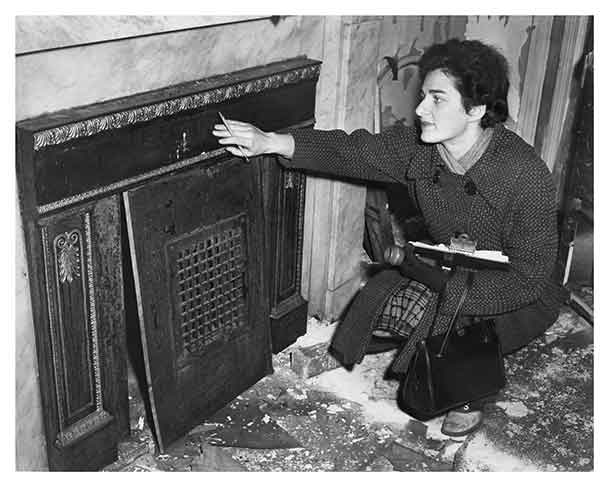

Nancy Pearsall

Nancy Pearsall

Brooklyn Heights residents Otis Pratt Pearsall and Nancy Pearsall became driving forces in the preservation efforts of the Brooklyn Heights Association (BHA) and the Community Conservation and Improvement Council (CCIC) in the late 1950s. Here, they document the interior of a Brooklyn Heights townhouse.

Image Info: 1950s, Courtesy Otis Pearsall.

Objects & Images

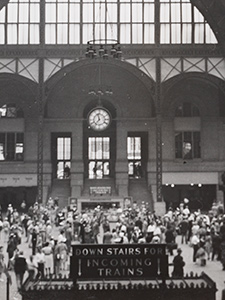

Interior, Penn Station

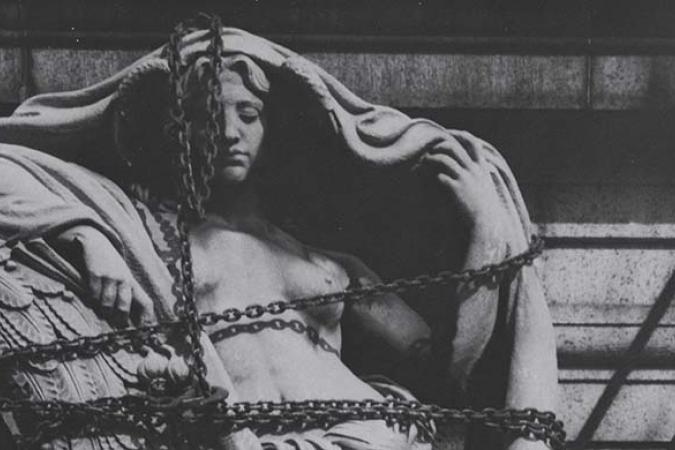

Interior, Penn Station

Architects and other New Yorkers prized McKim, Mead & White’s Penn Station interior for its masterful use of space and light. But without a city landmarks law in place, their appreciation could not save it from demolition.

Image Info: 1994, Museum of the City of New York, Gift of the Department of Local Government, Public Record Office of South Australia, 90.28.10.

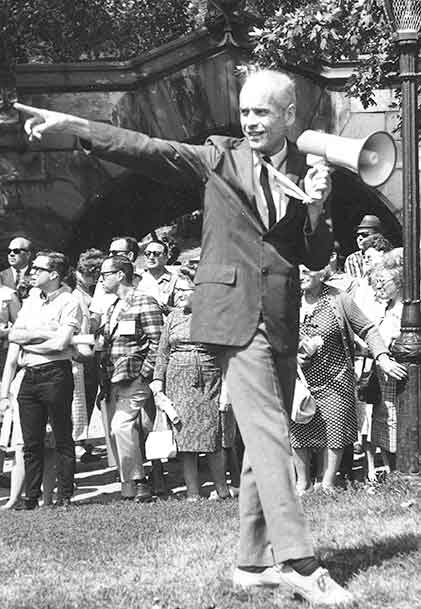

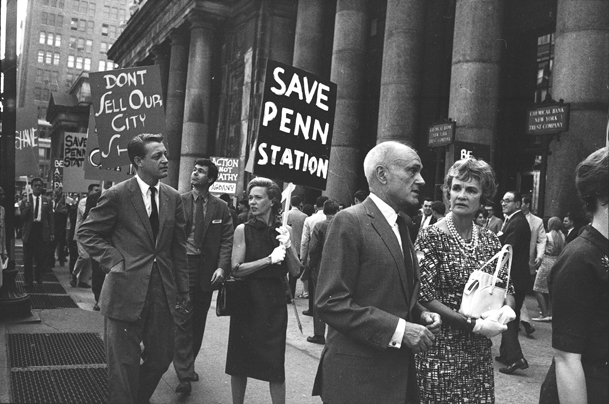

The Action Group For Better Architecture New York (agbany) Demonstrates Against The Scheduled Demolition Of Pennsylvania Station

The Action Group For Better Architecture New York (agbany) Demonstrates Against The Scheduled Demolition Of Pennsylvania Station

In 1956, landmarks activists were emboldened by New York State’s passage of the Bard Act, which gave cities the power to pass landmarks protection laws. Young architects and other professionals formed the Action Group for Better Architecture in New York (AGBANY) in October 1962 to protest the planned demolition of Penn Station.

Image Info: David L. Hirsch, ca. 1962, Courtesy of the photographer.

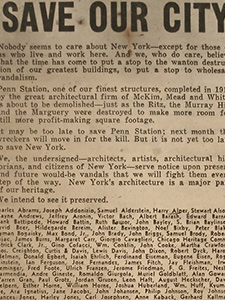

Save Our City

Save Our City

“It may be too late to save Penn Station,” AGBANY acknowledged in this petition. “But it is not yet too late to save New York.” The loss of Penn Station and of Fifth Avenue’s Brokaw Mansion in 1964-1965 sparked the public outcry that finally led to the Landmarks Preservation Law in 1965.

Image Info: Courtesy Peter Samton, FAIA, Action Group for Better Architecture in New York (AGBANY), 1962.

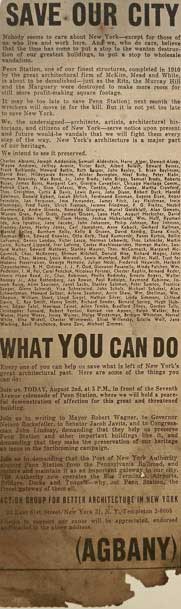

The Demolition Of Pennsylvania Station

The Demolition Of Pennsylvania Station

The Pennsylvania Railroad announced it would demolish Penn Station in 1962, and despite protests, the building was torn down between 1963 and 1966.

Image Info: Aaron Rose, 1964-1965, Museum of the City of New York, Gift of Aaron Rose, 2001.30.117.

The Demolition Of Pennsylvania Station

The Demolition Of Pennsylvania Station

Image Info: Aaron Rose, 1964-1965, Museum of the City of New York, Gift of Aaron Rose, 2001.30.78.

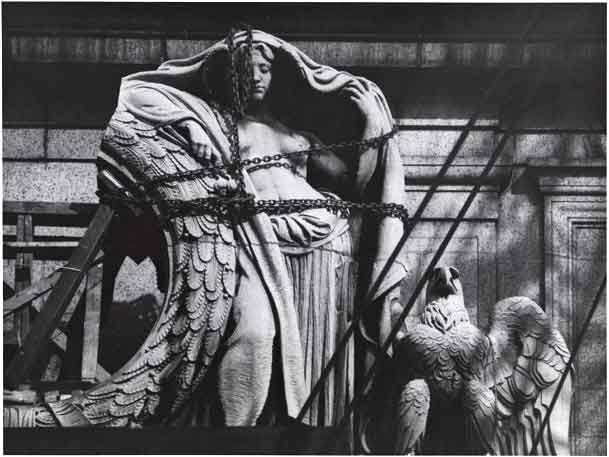

Hand-drawn Map Of Brooklyn Heights

Hand-drawn Map Of Brooklyn Heights

Collecting data on individual landmarks was a key tactic of New York’s preservation activists as early as the 1940s. Within a decade, advocates were also documenting entire neighborhoods such as Brooklyn Heights, Greenwich Village, and Gramercy Park. This map, showing the architectural styles of different buildings, was used by preservationists Otis and Nancy Pearsall at public hearings to illustrate the large number of 19th-century structures in Brooklyn Heights and the need to designate the neighborhood as a special landmarks district.

Image Info: ca. 1960, Courtesy Brooklyn Historical Society.

Letter From Otis Pearsall To George Hopper Fitch

Letter From Otis Pearsall To George Hopper Fitch

Advocacy for historic and aesthetic landmarks went hand in hand with concerns about overdevelopment and the quality of life in residential neighborhoods, as this letter from Otis Pratt Pearsall to George Hopper Fitch of the Municipal Art Society indicates.

Image Info: 1959, Courtesy Otis Pearsall.

"House At Willow & Middagh, Federal Style,” And "#2 Pierrepont St."

"House At Willow & Middagh, Federal Style,” And "#2 Pierrepont St."

The assistant librarian at what is now the Brooklyn Historical Society took these images to document Brooklyn Heights’ threatened heritage. Community groups used inventories of landmarks to press the City Planning Commission to designate their neighborhoods as special historic districts.

Image Info: John D. Morrell, 1958, Courtesy the Brooklyn Historical Society, V.1974.4.249 and V.1974.4.4.

View Of West Side Of Willow Street, Looking North Toward Pineapple

View Of West Side Of Willow Street, Looking North Toward Pineapple

Librarian and preservationist John D. Morrell continued to document historic buildings in the early 1960s. Inventories, photographs, and maps served as raw material for newsletters, newspaper articles, books, and public hearings that broadened public awareness and confronted city officials with hard evidence of the need to preserve historic buildings and pass a landmarks law.

Image Info: John D. Morrell, 1962, Courtesy the Brooklyn Historical Society, V1974.9.330.

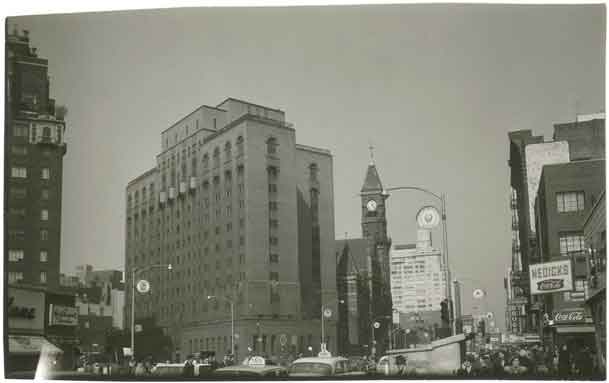

Women’s House Of Detention, Greenwich Ave Between 6th Ave. And W. 10th St., Northward On 6th Is The 1876 Jefferson Market Courthouse

Women’s House Of Detention, Greenwich Ave Between 6th Ave. And W. 10th St., Northward On 6th Is The 1876 Jefferson Market Courthouse

In the early 1960s, Greenwich Village writer and community activist Margot Gayle took snapshots of Manhattan buildings she believed to be threatened by real estate development. Accompanied by careful notes, her photographs documented landmarks that were later destroyed, such as the Women’s House of Detention, as well as several that were saved.

Image Info: Margot Gayle, ca. 1961, Courtesy the New-York Historical Society.

Germania Bank, Central Savings Bank, Se Corner Fourth & 14th, Built 1872

Germania Bank, Central Savings Bank, Se Corner Fourth & 14th, Built 1872

In 1961, Mayor Robert Wagner gave activists a new goal when he announced the appointment of a special committee to study the landmarks issue. For advocates, the prize—a citywide law—finally seemed within reach. Greenwich Village writer and community activist Margot Gayle’s own crusades safeguarded Jefferson Market Courthouse and helped lead to the designation of the SoHo-Cast Iron Historic District in 1973.

Image Info: Margot Gayle, ca. 1961, Courtesy the New-York Historical Society

Key Events

| Global | Year | Local |

|---|---|---|

|

|

1941 | Municipal Art Society compiles first list of threatened historic buildings in New York City |

| 1947 |

New Yorker George McAneny helps establish National Council for Historic Sites and Buildings |

|

| 1949 |

Preservationists win battle against Robert Moses to save Battery Park |

|

|

Bard Act allows for the protection of structures of “special historical or aesthetic value” |

1956 |

|

| 1958 |

Community Conservation and Improvement Council is formed and works with Brooklyn Heights Association for preservation of Brooklyn Heights landmarks |

|

| 1960 | Citizen’s Committee for Carnegie Hall forms non-profit corporation to save the Hall from demolition | |

| 1961 | Mayor Robert Wagner appoints Committee for the Preservation of Structures of Historic and Esthetic Importance | |

| 1962 | Protesters from Action Group for Better Architecture in New York (AGBANY) picket against proposed demolition of Pennsylvania Station |